- How Much Weight Can You Realistically Lose in 3 Months? - January 14, 2024

- How To Lose 1kg a Week (Guaranteed) - August 20, 2023

- How To Count Calories (or Estimate) and Stay on Track When Eating Out at Restaurants - July 25, 2023

No, most people should be able to handle a 1,000 calorie deficit, at least for a few months. In theory, a 1000 calorie per day deficit would result in around 1kg or 2lbs of weight loss per week. Just implementing a 1000 calorie deficit and sticking to it isn’t as simple as it sounds, however. This level of deficit requires dedication, willpower, and consistency.

DAILY OR WEEKLY?

When talking about the magnitude of a calorie deficit, it is very important to define the time period – a daily 1000 calorie deficit is VERY different from a weekly 1000 calorie deficit and will result in much quicker weight loss, but it’s also much more difficult to maintain.

A weekly deficit of 1000 calories would mean a daily deficit of 143 calories. This would only result in around 0.1kg of weight loss per week.

While a daily deficit of 1000 is quite aggressive, a weekly deficit of 1000 is probably too conservative for most in that the level of loss that it would produce in the short term is so low that it may cause the dieter to become demotivated.

HOW MUCH WEIGHT WOULD YOU LOSE ON A 1,000-CALORIE DEFICIT?

1kg of fat contains around 7,700 calories.

This means that a daily calorie deficit of 1000 would in theory result in a loss of 0.9kg per week.

This would mean a loss of 3.6kg per month, or 43kg a year.

Of course this is all theoretical – if you get all of your numbers spot on there’s no reason this wouldn’t happen, but getting everything spot-on on a consistent basis is easier said than done.

WANT TO KNOW HOW TO WORKOUT YOUR CALORIE DEFICIT? DROP YOUR EMAIL BELOW AND I’LL SEND YOU THE GUIDE

IS A 1,000 CALORIE DEFICIT TOO MUCH?

This all depends on a few different factors;

Discipline and Willpower

The first is how much discipline and willpower you have – if you don’t get cravings for high calorie foods like nuts, peanut butter, chocolate, cheese and alcohol, OR you don’t live with anyone that buys and consumes these kinds of foods regularly then you may be in good stead to a achieve a 1,000 a day deficit.

Similarly, if you have a packed social calendar full of events that revolve around food (dinner parties, meals out, weddings, work dinners etc) then sticking to this kind of deficit may prove to be very difficult unless you’re prepared to miss out on high calorie food and alcohol.

Your Starting Weight

A heavier person will have more weight to lose, and so will be able to afford to have a much larger deficit. Let’s say you weigh 100kg. You might maintain your weight on 2,800 calories per day.

This means that if you implement a 1,000 calorie deficit, you’ll still be eating 1,800 calories per day, fairly low, but not unbearable.

Now, let’s say you weigh 60kg, you may only maintain your weight on 1,800 calories per day so if you go for a 1,000 deficit, this means eating just 800 calories per day on average – that’s going to be tough for anyone.

So, a large deficit will be easier to stick to and therefore more suitable for heavier individuals and/or individuals that have a very high activity level.

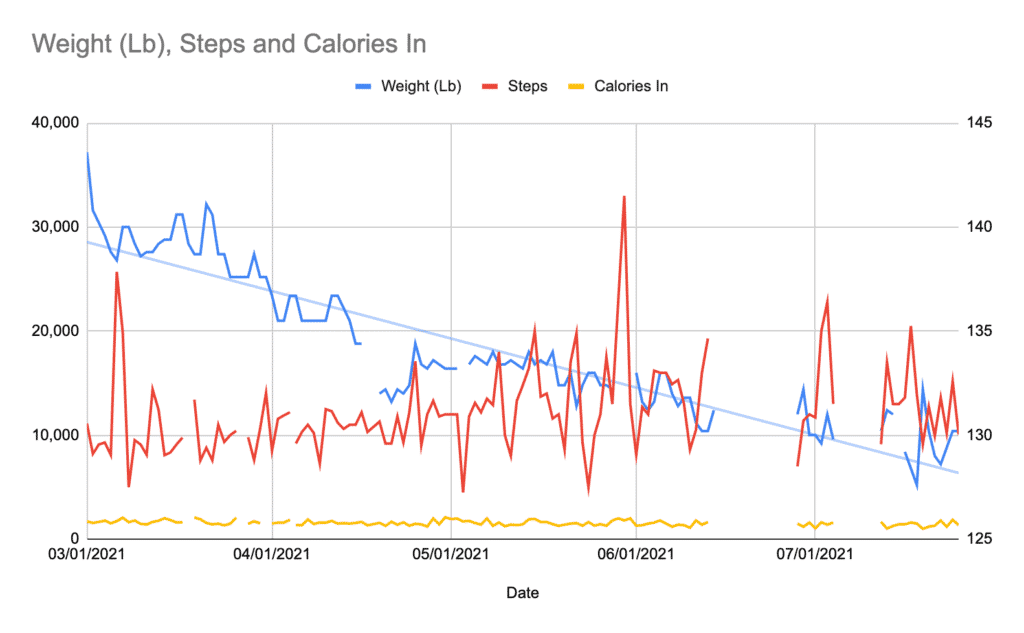

Below you can see the weight loss progress of one of my clients who lost 13.6lbs (6kg) across her whole journey – this only equated to 0.7lbs or 0.3kg per week on average, but this because their starting weight was very low, os there wasn’t scope to drastically decrease calories and have a large deficit – the end result is still a positive one though!

Your ‘Why’

If you have a clear ‘why’ for your weight loss goal – i.e. ‘I want to lose 5kg in 4 months so I look great in my holiday photos’ then you’ll be much more motivated to stick to a large deficit. The vision of you looking lean and tanned on the beach is likely to get you through the more difficult periods of the diet.

If your why is a little less clear and specific, i.e. ‘ I just want to lose a little bit of weight’ then sticking to large deficit is going to be much more challenging because your end goal is ambiguous.

Current Lifestyle

On the flip side, if you work part-time, or work fully remotely and don’t have such a busy life, planning your diet can be much easier as there are fewer spontaneous opportunities to just ‘grab something’ on your way to the office, so sticking to a large deficit may be easier

If you have a busy lifestyle that involves a hectic job, kids, a social life and hobbies then sticking to a large deficit will be more difficult because you’ll simply have less headspace to dedicate to dieting. The flipside of this is that you’ll likely be on your feet a lot which means you’ll naturally burn more calories through NEAT (non-activity exercise thermogenesis) so it CAN work in your favour.

THE BEST WAY TO APPROACH A 1,000-CALORIE DEFICIT

The best way to approach a large deficit (or any deficit) is to do so flexibly.

This means not necessarily eating the exact same amount of calories every day.

Let’s say for example that you maintain your weight on 2,300 calories, so you give yourself a daily average budget of 1,300 calories.

Rather than aiming for exactly 1,300 calories, you can instead spread this over the week, and shoot for a weekly total of 9,100 calories.

This means that you can zigzag your calories each day of the week, for example, you could eat 1,300 calories on Mon through to Friday, then have 2,000 on Saturday (700 calories over), followed by 600 on Sunday (700 calories under).

Doing this would still mean you hit the daily average of 1,300 but you get to enjoy a ‘cheat meal’ (if you want to call that) on Saturday.

This is exactly what one of my clients does – below is real data from one of my clients whose target is 1,800 calories per day on average – they did go slightly over on this particular week but you can see how calories are manipulated throughout the week to achieve the target.

| Day | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday |

| Date | 5-Jul-21 | 6-Jul-21 | 7-Jul-21 | 8-Jul-21 | 9-Jul-21 | 10-Jul-21 | 11-Jul-21 |

| Weight (kg) | 73.1 | 72.8 | 70.8 | 69.3 | 67.8 | 70.6 | 70.5 |

| Active Energy (kcal) | 387 | 1,982 | 2,098 | 1,184 | 785 | 3,177 | 575 |

| Calories In (kcal) | 1,244 | 1,131 | 1,196 | 1,306 | 2,297 | 2,169 | 3,569 |

CAN YOU STICK TO A 1,000-CALORIE DEFICIT LONG TERM?

Probably not, although it depends how you define the long term.

If we are talking a year, it’s highly unlikely anyone could maintain that large of a deficit for that amount of time.

Of course it is possible, it would just take a LOT of dedication.

You need to ask this question within the context of your current weight as well.

Sticking to an average daily calorie deficit of 1,000 would mean losing 43kg in a year – if you started off weighing 80kg that means you’d end up at 37kg which is of course dangerously underweight.

If you started off at 130kg however, losing 43kg would bring you down to 87kg which is a perfectly healthy weight for most people.

So it really depends, but for the most part, I wouldn’t recommend maintaining a deficit of that size for longer than a few months.

WILL “STARVATION MODE” KICK IN?

No, starvation mode won’t sabotage your efforts, starvation mode isn’t actually real, so you’ve no need to worry about it. What could happen however is that if you stick to a 1,000 calorie deficit for a long time, you might end up getting so hungry that you do overeat, which takes you out of a deficit altogether and causes weight loss to plateau.

This is why you need to choose the size of your diet carefully before you start dieting. Yes, bigger deficits do mean faster weight loss but on the flipside, they’re harder to stick to. You’re far better off with a smaller deficit, like a 500 calorie deficit for example that you can stick to for months, than a 1,000-calorie deficit that you can’t maintain for more than a few weeks.

WHAT ABOUT WEIGHT REGAIN?

The best way to diet is sustainably, i.e. in a way that you could conceivably manage to do for the rest of your life.

This means not cutting out carbs, or not eating after 6pm, and crucially, not eating super low calories.

For a lot of people, a deficit of 1,000 per day could be perceived as ‘super low’. It also means eating in a way that may not be consistently sustainable.

So actually, going too low could be shooting yourself in the foot if it means going back to way you were eating before.

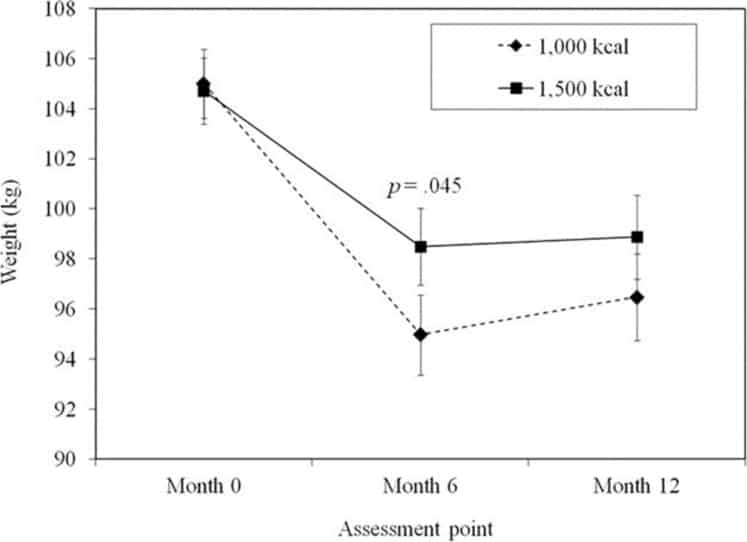

In fact, this study on 125 obese women divided the group into two – one was given 1,000 calories per day and one 1,500 calories per day. It found that;

“participants with baseline intakes ≥2,000 kcal/day who were assigned 1,000 kcal/day were significantly more susceptible to weight regain than those assigned 1,500 kcal/day”

Nackers et al, 2013

CONCLUSION

For most people, a calorie deficit of 1,000 per day is going to be too low. There are of course exceptions, i.e. if you are very active or very overweight to start with.

If you want to know what the best size deficit for you is, you should work with a weight loss coach who can help you plan out and stick to your diet to make sure you achieve what you want.

REFERENCES

Effects of Prescribing 1,000 versus 1,500 Kilocalories per Day in the Behavioral Treatment of Obesity: A Randomized Trial https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC57712

Leave a Reply